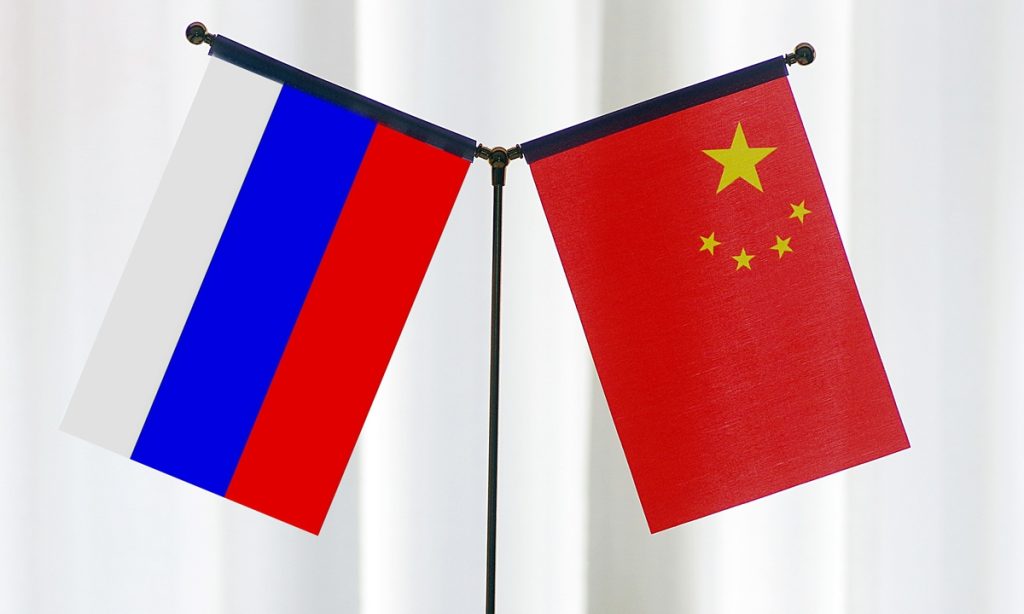

China, Russia won't mind US attitude to enhance strategic consultations: Global Times editorial

At the invitation of Secretary Nikolai Patrushev of the Security Council of the Russian Federation, Wang Yi, member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and director of the Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission of the CPC Central Committee, is visiting Russia from September 18 to 21 and attending the 18th round of China-Russia strategic security consultation. Since the establishment of the China-Russia strategic security consultation mechanism in 2005, initiated by the leaders of the two countries, consultations are held annually in principle, though the dates are flexible. This is an example of high-level communication mechanisms between China and Russia, and there are many similar mechanisms.

What is the focus of this consultation? This question has garnered extensive attention in the current exceptionally complex international environment, which includes the long-standing Ukraine crisis, unusual actions of the US, Japan, and South Korea in the Northeast Asia region, the collective rise of emerging economies demanding a more just and equitable international order, and more. In many of these areas, China and Russia, as two major global powers, play pivotal roles. In a certain sense, the China-Russia relationship will fundamentally influence peace and stability not only in the region but also the entire international community.

This consultation, which took place immediately after Wang's multiple rounds of meetings with US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in Malta on September 16 and 17, has attracted more attention from Western media, leading to various interpretations. However, many of these interpretations are distorted and biased. For example, some Western media outlets have seized upon the coincidental timing of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un's recent visit to Russia and Wang's trip to Russia for the strategic security consultations as fodder for promoting a "China-Russia-North Korea axis." This is a typical narrative of a "new cold war," and it is necessary to set the record straight on this matter.

China-Russia relations have been seriously stigmatized by Western media, and this has become an increasingly apparent and clear part of Western countries' public opinion strategy or cognitive warfare. They aim to portray China, Russia, and other countries like North Korea, which face containment and suppression from the West, as a collective "axis of power" that threatens the so-called "free world." Within this narrative framework, every interaction between China and Russia, China and North Korea, Russia and North Korea, and related countries is branded as part of an effort to establish and strengthen this "axis," as if every interaction is a conspiracy against the US. This is a psychological illness. The root of the problem lies in Washington's attempt to introduce a "new cold war" into Northeast Asia. As a result, it feels insecure and tries to project its own actions onto others, leading to absurd conclusions.

International perception may be temporarily confused by noise, but one fact that is not hidden is that we are described as "an axis," "a group," or "an alliance." This definition is fundamentally different from the real relationship between China and Russia, or China and North Korea. China pursues an independent and peaceful foreign policy, emphasizing "partnership rather than alliance" in its diplomatic relations. It also practices comprehensive diplomacy, aiming to peacefully coexist and achieve win-win cooperation with all countries in the world. Whether it is China's attitude toward Russia or the US, it has always been consistent and stable, which is to engage with others with the utmost goodwill and sincerity for cooperation. Currently, the US and a few Western countries are strengthening their group politics and engaging in camp confrontation. In order to justify and legitimize this behavior that is unpopular in the international community, they are attempting to create an opposing group, and the media has acted as the vanguard.

Chinese diplomacy firmly opposes such stigmatization and demonization. Meanwhile, we steadfastly promote relations with any friendly country toward China, especially the China-Russia relationship, and will not be constrained by external malicious rhetoric. The comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era between China and Russia has a strong internal driving force. The complex changes in the international situation and pattern serve as the external environment for strengthening strategic coordination and practical cooperation between China and Russia. The stable, predictable, and continuously advancing China-Russia relationship is important for both countries and the world.

Chinese diplomacy is willing to devote more energy and resources to strengthen, consolidate, and further develop bilateral relationships with certainty, such as the China-Russia relationship. Both China and Russia are major countries with strong strategic autonomy, and their interactions are open and aboveboard, which will by no means succumb to Washington's influence. It is advised that those who are busy speculating on "secret deals" between China and Russia should spend some time understanding what the interaction between major countries should actually be like, rather than engaging in various assumptions.