Shhhh! Some plant-eating dinos snacked on crunchy critters

Some dinosaurs liked to cheat on their vegetarian diet.

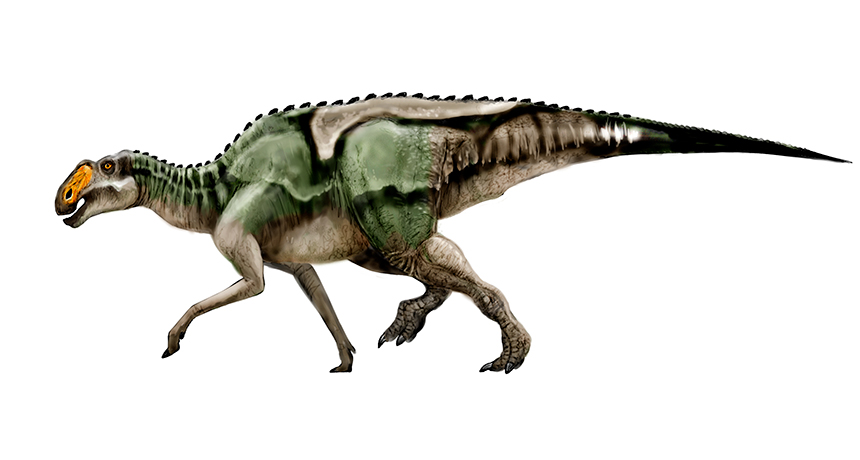

Based on the shape of their teeth and jaws, large plant-eating dinosaurs are generally thought to have been exclusively herbivorous. But for one group of dinosaurs, roughly 75-million-year-old poop tells another story. Their fossilized droppings, or coprolites, contained tiny fragments of mollusk and other crustacean shells along with an abundance of rotten wood, researchers report September 21 in Scientific Reports. Eating the crustaceans as well as the wood might have given the dinosaurs an extra dose of nutrients during breeding season to help form eggs and nourish the embryos.

“Living herd animals do occasionally turn carnivore to fulfill a particular nutritional need,” says vertebrate paleontologist Paul Barrett of the Natural History Museum in London. “Sheep and cows are known to eat carcasses or bone when they have a deficiency in a mineral such as phosphorus or calcium, or if they’re pregnant or ill.” But the discovery that some plant-eating dinos also ate crustaceans is the first example of this behavior in an extinct herbivore, says Barrett, who was not involved in the new study.

Ten years ago, paleoecologist Karen Chin of the University of Colorado Boulder described finding large pieces of rotted wood in dino dung. The coprolites were within a layer of rock in Montana, known as the Two Medicine Formation, dating to between 80 million and 74 million years ago. That layer also contained numerous fossils of Maiasaura, a type of large, herbivorous duck-billed dinosaur, or hadrosaur (SN: 8/9/14, p. 20).

Chin wondered whether the wood itself was the dino’s real dietary target. “The coprolites in Montana were associated with the nesting grounds of the Maiasaura ,” she says. “I suspected that the dinosaurs were after insects in the wood. But I never found any insects in the coprolites there.”

Her hunch wasn’t too far off. Now she’s found evidence of some kind of crustaceans in dino poop. The new evidence comes from an 860-meter-thick layer of rock in Utah known as the Kaiparowits Formation, which dates to between 76.1 million and 74 million years ago. Ten of the 15 coprolites that Chin and her team examined contained tiny fragments of shell that were scattered throughout the dung. They were too small to identify by species, and may have been crabs, insects or some other type of shelled animal, Chin says. Based on the scattering of shell fragments, the animals were certainly eaten along with the wood rather than being later visitors to the dung heap.

Since bones from hadrosaurs are especially abundant in the Kaiparowits Formation, Chin suspects those kinds of dinos deposited the dung. Other large herbivores, such as three-horned ceratopsians and armored ankylosaurs, also roamed the area (SN: 6/24/17, p. 4).

The crustacean diet cheat may have been a seasonal event, related perhaps to breeding to obtain extra nutrients, Chin and colleagues say.

But how often — or why — the dinosaurs ate the shelled critters is hard to prove from the fossil dung alone, Barrett says. Herbivore coprolites are rare in the fossil record because a diet of leaves and other green plant material doesn’t leave a lot of hard material to preserve (unlike bones in carnivore dung). Coprolites with crustaceans, on the other hand, are more likely to get fossilized — and that preferential preservation might make it appear that this behavior was more frequent than it actually was. “These kinds of things give neat snapshots of specific behaviors that those animals are doing at any one time,” he adds. “But it’s difficult to build that into a bigger picture.”